Sign of the Cross Prayer

Introduction

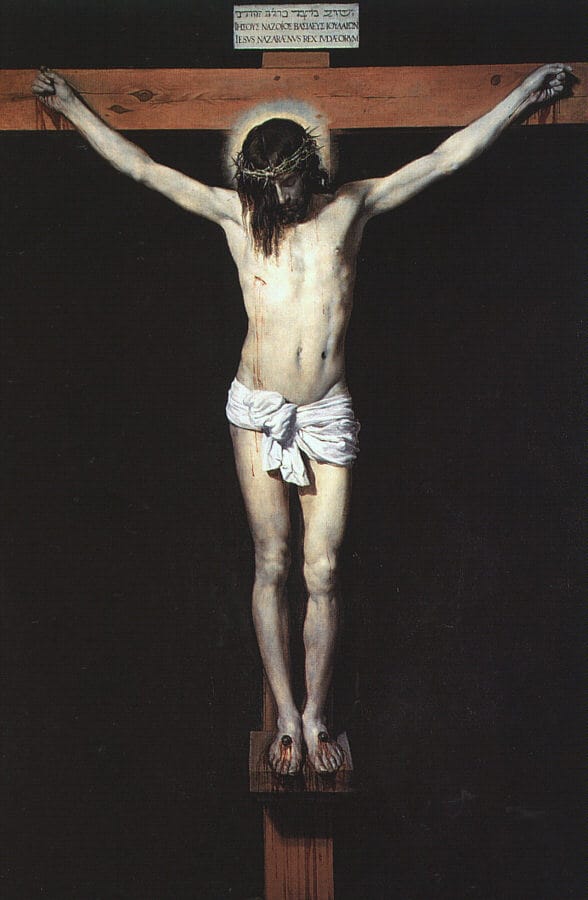

The Sign of the Cross is the doorway into the Rosary. Before a bead is touched, a person traces the Cross on their body and calls on the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, just as Our Lord commanded for Baptism, “in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost” (Mt 28:19). This simple act is a short profession of faith in the Trinity and in the saving Cross of Christ. It tells God, and reminds the soul, that the Rosary will be prayed in union with the Church and under the sign of Jesus’ sacrifice. For someone returning to prayer, or trying the Rosary for the first time, beginning with the Sign of the Cross gives a clear, humble way to start in faith.

The Rosary Begins with the Sign of the Cross

Catholics begin the Rosary with the Sign of the Cross because the prayer starts in the name and power of God, not in personal effort. By calling on the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, the person enters the Rosary under the mystery of the Trinity, as in Baptism “in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost”. Tracing the Cross recalls that every grace of the Rosary comes from Christ’s sacrifice (Gal 6:14). It is also an act of belonging: the person claims the Cross over mind, heart, and actions before meditating on the mysteries. This beginning turns the Rosary from a string of private thoughts into a clear act of Catholic prayer, offered with the whole Church.

Sign of the Cross as a Profession of Faith

The Sign of the Cross is a short, clear profession of faith that every Catholic can make in a moment. When a person says, “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost,” they confess belief in the one God in three divine Persons, just as the Lord commanded for Baptism. Tracing the Cross on the body proclaims faith that salvation comes through the Passion and Death of Jesus Christ. Even without many words, the gesture says: “I belong to the Father through the Son in the Holy Ghost.” The Catechism notes that Christians begin their day and prayers with the Sign of the Cross, placing their lives under God’s holy name (CCC 2157).

What This Guide Will Help You Understand

This guide will help the reader see the Sign of the Cross as more than a habit at the start of the Rosary. It will explain the words and gestures, show their links to Scripture and the teaching of the Church, and highlight what the Sign of the Cross proclaims about the Trinity and the saving work of Christ. The reader will learn where this prayer fits into the structure of the Rosary and how to begin and end each Rosary with greater care. It will also offer practical help for praying the Sign of the Cross with mind, heart, and body, and for living under the sign of Christ’s Cross in daily life. Whether someone is returning to the Rosary or just beginning, this guide will give clear direction.

The Words and Gestures of the Sign of the Cross

In the Sign of the Cross, words and gesture belong together. The prayer is simple: “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.” As these words are spoken, the hand moves from the forehead to the breast, then from the left shoulder to the right. The Cross is traced on the body while the Trinity is named. The forehead is offered, with thoughts and plans; the breast is offered, with desires and affections; the shoulders are offered, with work and burdens. Saying “in the name” recalls the power of God’s name in Baptism, and “Amen” seals the act with faith. When the Sign of the Cross is made with care, the whole person is turned toward God.

The Sign of the Cross (Full Text)

In the Name of the Father,

and of the Son,

and of the Holy Spirit.

Amen.

How to Make the Sign of the Cross Step by Step

To make the Sign of the Cross, a person begins by using the right hand. First, touch the forehead and say, “In the name of the Father,” offering God the mind and thoughts. Then move the hand down to the breast and say, “and of the Son,” recalling that the Son took our flesh and dwelt among us (Jn 1:14). Next, touch the left shoulder and say, “and of the Holy,” then the right shoulder and say, “Ghost,” remembering the Spirit who strengthens and consoles the Church (Jn 14:26). Finally, fold the hands or place them together and say, “Amen,” to seal this act of faith. The gesture is done slowly and clearly, without haste, as a short but real prayer.

Forehead: Marking the Mind with the Cross

When the Sign of the Cross begins at the forehead, the believer is offering their mind to God. Touching the forehead and saying, “In the name of the Father,” places thoughts, plans, and judgments under the light of the Father’s wisdom. It is a quiet prayer that ideas and memories may be purified, that faith may guide every decision. Scripture speaks of the “renewing of your mind” so that you may “prove what is the will of God” (Rom 12:2). Marking the forehead with the Cross also recalls the servants of God sealed on the forehead in the Apocalypse (Apoc 7:3). In a simple gesture, the person asks that all thinking be marked by the Cross of Christ before entering the Rosary.

Breast: Marking the Heart with the Cross

When the hand moves from the forehead to the breast, the person is offering the heart to God. Saying “and of the Son” while touching the chest recalls that the Son took a human Heart that loves, suffers, and is pierced for our salvation (Jn 19:34). This simple gesture can be a quiet act of surrender: the joys, fears, wounds, and attachments of the heart are placed under the Cross. God promises to give a “new heart” and put a “new spirit” within His people (Ezek 36:26). Marking the breast with the Cross is a way of asking for that promise again, so that love may be purified and ordered to Christ. Before beginning the Rosary, the believer entrusts all affections to the Heart of Jesus.

Shoulders: Embracing the Cross Daily

When the hand moves from the left shoulder to the right and the words “and of the Holy Ghost” are spoken, the believer offers daily burdens to God. The shoulders carry weight; they suggest work, duty, and the cares that press on a person. By tracing the Cross across the shoulders, the Catholic quietly joins these burdens to Christ, who calls each disciple to “take up his cross daily” and follow Him (Lk 9:23). At the same time, the Holy Ghost is invoked, who strengthens, consoles, and makes Christ’s yoke sweet (Mt 11:28–30). In this part of the Sign of the Cross, ordinary labor, family concerns, and hidden sufferings are placed under the Cross so that the Rosary can be prayed in a spirit of trust and offering.

Saying "Amen" with Faith and Surrender

The last word of the Sign of the Cross, “Amen,” is not a formality. It means “so be it,” or “it is true.” When a Catholic says “Amen” after naming the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost and tracing the Cross, they give personal consent to all that has just been professed. It is a simple act of faith: “I believe this, and I place myself under it.” In Scripture, “Amen” is a word of strong agreement with God’s promises in Christ (2 Cor 1:20). It is also an act of surrender: the mind, heart, and daily burdens marked by the Cross are now entrusted to God’s holy will. Beginning the Rosary with a sincere “Amen” lets the whole prayer rest on trust.

Common Variations in Gesture and Wording

Across the Church, Catholics make the Sign of the Cross in slightly different ways, yet they confess the same faith. In the Latin tradition, most begin at the forehead, then touch the breast, left shoulder, and right shoulder. Some add a small cross on the forehead, lips, and breast before the Gospel at Mass. Eastern Catholics trace it from the right shoulder to the left and often hold the fingers together in a way that recalls the Trinity and the two natures of Christ. The wording also varies: “Holy Ghost” or “Holy Spirit,” English or Latin, sometimes followed by short invocations, such as “My Jesus, mercy.” The Church does not demand strict uniformity in these small details. What matters is that the Sign of the Cross is made with faith, reverence, and love.

Teaching Children

Teaching children the Sign of the Cross is one of the first works of family catechesis. They learn best by watching, so parents and grandparents should make the Sign of the Cross slowly and clearly, inviting the child to copy. At first, an adult may gently guide the child’s hand from forehead to breast, shoulder to shoulder, saying the words aloud in a calm voice. It helps to give a short, simple meaning: “We are saying we belong to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.” Repeating the gesture at the morning, at bedtime, at meals, and before the Rosary lets it sink into the child’s memory. Even if the motions are clumsy at first, the adults’ care and reverence will teach the child that this little prayer is holy.

Biblical and Historical Foundations

The Sign of the Cross grows from Scripture and the life of the early Church. In the Old Testament, God commands a mark on the forehead of His faithful as a sign of protection (Ezek 9:4). Saint Paul glories only “in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ”, and Saint John shows the servants of God sealed on their foreheads. From the earliest centuries, Christians traced a small cross on their foreheads before prayer and in times of danger; writers like Tertullian and Saint Cyril of Jerusalem describe this custom. Over time, the gesture grew into the larger Sign of the Cross used today, joining the forehead, breast, and shoulders while the Trinity is named. The same faith remains: salvation comes through Christ’s Cross, confessed with mind, heart, and body.

The Sign in Sacred Scripture

Scripture does not give the exact gesture of the Sign of the Cross, but it shows signs on the body that prepare the way for it. In Ezechiel, the Lord commands a mark on the foreheads of those who sigh for sin so that they will be spared in judgment. In the Apocalypse, the servants of God are sealed on their foreheads as His own. Saint Paul speaks of glorying only “in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ”. Christ sends the apostles to baptize “in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost”. Taken together, these texts show a marked people, claimed by the Cross and the Trinity, which the Sign of the Cross expresses in gesture and prayer.

The Early Church and Fathers

The early Christians quickly learned to trace the Cross on their bodies as a daily confession of faith. Tertullian, in the third century, says that Christians signed themselves on the forehead at every step and action, before meals, travel, and rest, as a quiet claim to Christ’s protection. Later, Saint Cyril of Jerusalem urges the faithful not to be ashamed of the Cross, but to sign it boldly on the brow in every situation, as a shield in temptation and fear. Other Fathers speak of the Cross as the banner of the Christian, the mark that separates the believer from the Spirit of the world. These early witnesses show that long before formal Rosary prayers, the Sign of the Cross was a familiar, constant prayer in the Church.

Growth of the Practice in the Latin Rite

In the Latin Rite, the Sign of the Cross grew from a small, simple gesture into the fuller form Catholics know today. At first, Christians often traced a small cross only on the forehead. Over time, especially in the Middle Ages, the gesture expanded to include the breast and shoulders, expressing with the whole upper body the shape of the Cross and the naming of the Trinity. The blessing given by the priest at Mass, with a large Sign of the Cross over the people, helped form this pattern. Gradually, the faithful began to copy that gesture in their own prayer, at home and in Church. By the time the Rosary spread widely, beginning prayer with the Sign of the Cross was already a long-standing custom in the Latin Church.

Eastern Catholic and Orthodox Traditions

In Eastern Catholic and Orthodox traditions, the Sign of the Cross is made with a different gesture but the same faith. The thumb, index, and middle fingers are held together to honor the Trinity, while the ring and little fingers bend toward the palm to recall the two natures of Christ. The hand then moves from the forehead to the breast, but from the right shoulder to the left. Eastern Christians sign themselves very often: entering the Church, venerating icons, before and after meals, and many times during the Divine Liturgy. The gesture is slower and more deliberate, often joined to a bow or a slight inclination. For Latin Catholics, learning about this practice can deepen respect for the Cross and show the shared confession of Father, Son, and Holy Ghost across the Church.

What the Sign of the Cross Proclaims

The Sign of the Cross is a small act that announces the whole Catholic faith. When a person says, “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost,” they proclaim belief in one God in three divine Persons, as taught by Christ Himself. Tracing the Cross on the body declares that salvation comes through the Passion and Death of Jesus, not through human strength. The gesture also says: “I belong to Christ and to His Church.” It claims the mind, heart, and daily work for God and rejects the power of sin and the devil. Each time a Catholic makes this Sign, in the Rosary or at any moment, the faith of Baptism is quietly proclaimed again.

Confessing the Most Holy Trinity

Each time a Catholic makes the Sign of the Cross, he confesses the mystery of the Most Holy Trinity. Saying, “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost,” uses the singular “name,” not “names,” because there is one God in three divine Persons. The gesture is like a small creed done with the body. The Father is confessed as source of all, the Son as the Word made flesh who died on the Cross, and the Holy Ghost as the Spirit who gives life to the soul (Jn 1:14; Jn 6:63). This short prayer carries the same faith expressed in the Church’s creeds, but in a way any believer can make in a moment, before the Rosary or at any time of day.

Remembering the Incarnation and the Holy Name of Jesus

The Sign of the Cross also remembers the Incarnation and the holy Name of Jesus. When a person says “and of the Son” while tracing the Cross on the body, he recalls that the eternal Son took our flesh and entered our history, “and the Word was made flesh” (Jn 1:14). In many prayers, this gesture is joined to the Name of Jesus, “for he shall save his people from their sins” (Mt 1:21). Saint Paul teaches that God has given Him “a name which is above all names” and that “at the name of Jesus every knee should bow” (Phil 2:9–10). Making the Sign of the Cross with faith is a small act of reverence for this saving Name and for the Son who became man for our salvation.

The Cross, Salvation, and Spiritual Warfare

The Sign of the Cross is not only a reminder of doctrine; it is also a weapon in spiritual warfare. When a Catholic traces the Cross and names the Trinity, he claims again the victory of Christ, who saved us by His Passion and Death. On the Cross, Christ “despoiled principalities and powers” and triumphed over them (Col 2:15). The Church uses the Sign of the Cross in blessings, in the rites of Baptism, and in exorcisms, because the devil fears the power of the Crucified and Risen Lord (CCC 1673). When a person makes this Sign with faith, temptations and fears are met under the standard of Christ. Beginning the Rosary with the Sign of the Cross places the whole prayer inside that saving victory.

Belonging to Christ and His Church

The Sign of the Cross is also a quiet claim of belonging. The baptized person has already been marked with the Cross and sealed as Christ’s own (CCC 1272–1274). When people trace that same Cross on the body and names the Trinity, it is a way of saying again, “I am Yours.” Saint Paul reminds the faithful that they are not their own, for they were “bought with a price” (1 Cor 6:19–20). This gesture is never just private devotion; it is an act of the Church, made in communion with all who confess the same faith. Beginning the Rosary with the Sign of the Cross helps the believer remember that each bead is prayed as a living member of Christ’s Body, not as an isolated soul.

The Sign of the Cross in the Rosary

In the Rosary, the Sign of the Cross is not just an extra gesture; it holds the whole prayer together. A person begins by taking the crucifix and making the Sign of the Cross, entering the Rosary in the same Trinitarian faith given at Baptism “in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost”. Only then does the sequence of prayers begin: Apostles’ Creed, Our Father, Hail Marys, and the decades that follow. Many Catholics also end the Rosary with the Sign of the Cross, as a final act of praise and trust. This means every Rosary is enclosed in the Cross and the holy name of God, from the first bead to the last.

Where the Sign of the Cross Occurs in the Rosary

The Sign of the Cross comes at the very beginning and usually at the very end of the Rosary. To start, a person takes the crucifix, makes the Sign of the Cross, and then prays the Apostles’ Creed. This first gesture opens the whole prayer in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. After that, the Rosary moves along the beads: Our Father, Hail Marys, Glory Be, and the decades of mysteries. When the final prayers are finished—often the Hail Holy Queen and any other closing prayers—many Catholics again make the Sign of the Cross. In this way, the Rosary begins and ends in the same simple act of faith, blessing, and self-offering.

Uniting the Sign of the Cross with the Apostles' Creed

At the start of the Rosary, the Sign of the Cross and the Apostles’ Creed belong together like body and voice. First, the Catholic traces the Cross and names the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, making a short profession of faith with the whole body. Then, holding the crucifix, they speak that same faith in detail through the Apostles’ Creed, which sums up what the Church believes and hands on (CCC 194–197). The Sign of the Cross is like a small doorway; the Creed is the full room of truth that lies beyond it. Prayed together, they help a person remember that the Rosary is not just a set of private devotions, but a prayer said in the faith of the universal Church.

Beginning the Rosary with Reverence and Intention

The way a person begins the Rosary often shapes the whole prayer. Before anything else, it helps to pause, quiet the mind, and stand or sit in a respectful posture. Then the Sign of the Cross is made slowly, followed by the Apostles’ Creed, said with care rather than from habit. Many Catholics briefly state an intention at this point: for loved ones, the souls in purgatory, the sick, the Church, or a personal struggle. This does not have to be long, but it should be honest. Beginning in this way tells God that the Rosary is not a mechanical task, but a free act of love and trust. The Sign of the Cross becomes the moment when the whole prayer is placed in His hands.

The Sign of the Cross at the End of the Rosary

At the end of the Rosary, the Sign of the Cross is a small but important act that closes the prayer in faith. After the Hail Holy Queen and any final prayers, the person traces the Cross and again calls on the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. This last gesture hands over every Hail Mary, every intention, and every distraction to God’s care. It is a way of saying, “I have prayed as best I can; now You take it.” The Sign of the Cross at the end also blesses the time that follows, asking that the graces of the mysteries touch the rest of the day. In this way, the Rosary begins and ends under the same sign of Jesus’ Cross and the Trinity’s love.

Praying the Sign of the Cross with Mind, Heart, and Body

Guarding Against Habit and Distraction

Because the Sign of the Cross is so familiar, it is easy to make it on “automatic,” with little thought or faith. To guard against this, it helps to slow down and remember who is being named. Before moving your hand, pause for a brief moment and call to mind the presence of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. If distractions come, do not be harsh with yourself; gently return to the words and the gesture. The Catechism teaches that distraction is a normal struggle in prayer and calls the believer to vigilance of heart (CCC 2729). Even choosing a few times each day to make the Sign of the Cross very carefully can renew the rest. Over time, this small effort keeps the prayer honest instead of empty.

Simple Ways to Slow Down and Pray with Attention

To pray the Sign of the Cross with attention, small changes can make a difference. Begin by taking a breath before you move your hand. In that short pause, remember that you are about to stand before the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. As you trace the Cross, say each phrase clearly and give a tiny pause after “Father,” “Son,” and “Holy Ghost.” From time to time, you might offer one Sign of the Cross very slowly, thinking only of one thing: the Trinity, the Cross, or your Baptism. It can also help to close your eyes, or to fix your gaze on a crucifix or icon. These simple habits cost little, but they keep the gesture from becoming empty and let the heart stay awake.

Making the Sign of the Cross in Moments of Suffering

In times of pain, fear, or confusion, the Sign of the Cross can become a short cry of trust. When illness flares, when news is heavy, or when the heart feels crushed, a person may not find many words—simply tracing the Cross and naming the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost places that suffering inside Christ’s own Passion. Our Lord calls His disciples to “take up his cross daily” and follow Him. Making the Sign of the Cross in that moment is a way of saying, “I accept this with You, not alone.” It can be done at a hospital bed, at a graveside, after a hard phone call, or in silent anxiety at night. This small gesture lets Christ’s victory touch very personal wounds.

Helping Family and Friends Deepen This Prayer

Helping others deepen the Sign of the Cross usually begins with quiet example, not long talks. When family and friends see it made slowly and with care, they are reminded that it is real prayer, not a nervous habit. At home, parents can invite children and guests to begin meals or the Rosary with a thoughtful Sign of the Cross, adding a short reminder from time to time: “Remember, we are calling on the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.” With older children or friends, a simple word of teaching can help: share one Scripture verse or a brief thought about the Cross or the Trinity (Mt 28:19; Gal 6:14). The goal is not to correct every careless gesture, but to encourage a deeper love for the God whose name is being invoked.

Living Under the Sign of the Cross Daily

Living under the Sign of the Cross means letting this small prayer shape the whole day. A Catholic can begin the morning with the Sign of the Cross, offering the coming hours to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Before work, driving, meals, or important tasks, the same gesture can quietly say, “Lord, this is Yours.” In moments of temptation or anger, tracing the Cross is a way to turn back to Christ, who loved us and “gave himself for me” (Gal 2:20). At night, making the Sign of the Cross before sleep entrusts the day’s sins, wounds, and joys to God’s mercy. Step by step, this simple prayer marks ordinary life as belonging to Jesus.

The Sign of the Cross in Ordinary Catholic Practices

The Sign of the Cross runs through ordinary Catholic life like a steady refrain. A person signs himself with holy water on entering and leaving the Church, recalling Baptism and asking for cleansing (Rom 6:3–4). Mass begins and ends with the Sign of the Cross, and the priest traces it often in blessings over the people, the Gospel book, and the gifts. At home, families use it before and after meals, before driving, at the start of work or study, and before sleep. Parents sign their children on the forehead at bedtime or when they are afraid. In Confession, Anointing of the Sick, and other sacraments, the Cross is traced again and again. These simple, repeated gestures quietly say that every part of life belongs to the Crucified and Risen Lord.

Public Witness: Before Meals, Travel, and Work

Making the Sign of the Cross in public is a quiet but strong witness. Before meals in a restaurant, a Catholic can bow the head, trace the Cross, and thank God for the food. On the road, signing oneself before driving asks the Lord’s protection and reminds the soul that every trip is under His care. At the start of work, a brief Sign of the Cross at a desk, in a truck, or on a job site can place the day’s labor in God’s hands. Some may feel awkward at first, but this small act often strengthens faith and encourages others. It tells the people nearby, without a speech, that God is real, that Christ has died and risen, and that His name can be confessed in daily life.

The Sign of the Cross and the Sacraments

The Sign of the Cross is closely tied to the sacraments, especially Baptism. A Catholic’s life in grace begins when the priest or deacon signs the child on the forehead and later pours water “in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost”. The Catechism teaches that this seal marks the Christian as belonging to Christ forever (CCC 1272–1274). In Confirmation, the bishop traces the Cross with holy chrism on the forehead. In the Eucharist, the priest signs the gifts and the people many times, recalling that every sacramental grace flows from Christ’s sacrifice on Calvary. In Confession and Anointing of the Sick, the Cross is retraced in blessing and pardon. When a Catholic makes the Sign of the Cross, he touches the very mark of his sacramental life.

Sign of the Cross at Life's End

At life’s end, the Sign of the Cross can be a last act of faith and hope. Many Catholics pray that they may die “in the grace of God and in the communion of the Church” (CCC 1861). When a dying person is able, slowly tracing the Cross or being signed by a priest or loved one can be a final “yes” to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. In the Church’s prayers for the dying, the Cross and the holy Name of Jesus are often invoked, because Christ has passed through death and opened the way to the Father (Heb 2:14–15). For those at the bedside, making the Sign of the Cross over the dying is a tender way of entrusting that soul to God’s mercy and asking for final perseverance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Scripture does not describe the full gesture of the Sign of the Cross as Catholics practice it today, but it does outline its main elements. Christ commands Baptism "in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost", which we echo each time we make the Sign. The Bible also speaks of God's servants being marked on the forehead as His own (Ezech 9:4; Apoc 7:3). Saint Paul glories in "the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ". The Church joins these biblical truths in one simple prayer of body and voice.

No. When Catholics make the Sign of the Cross, they are not worshiping a piece of wood or the shape of a cross. Worship (adoration) belongs to God alone. By tracing the Cross and naming the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, a person is worshiping God and recalling what Jesus did for us on Calvary. The Cross is a sign that points to Christ, His sacrifice, and His victory over sin and death. The gesture honors the Lord who died on the Cross, not the object itself.

Christians pray the Sign of the Cross differently because of diverse liturgical traditions, not different faiths. In the Latin (Roman) Rite, most trace from the forehead to the breast, then to the left shoulder to the right, usually saying "Holy Spirit" or "Holy Ghost." Eastern Catholics and Orthodox often join their fingers in a special way to show belief in the Trinity and the two natures of Christ, moving from right to left. Some Protestants do not use the gesture at all. What matters is the shared confession of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

Yes. Any person who believes in God, and especially in Jesus Christ, may make the Sign of the Cross. The gesture is not a secret mark for Catholics only; it is a short prayer calling on the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Non-Catholic Christians who share this faith can gladly use it to remember Baptism and the Cross. Someone who is searching or not yet baptized may also make the Sign of the Cross as a simple cry for light and help. The important thing is to do it with respect and honesty, not as a joke or superstition.

Links

Rosary Prayers

Charles Rogers is a resident of South Carolina and a retired computer programmer by trade. Raised in various Christian denominations, he always believed in Jesus Christ. In 2012, he began experiencing authentic spiritual encounters with the Blessed Virgin Mary, which led him on a seven-year journey at her hand, that included alcohol addiction, a widow maker heart attack and death and conversion to the Catholic Faith. He is the exclusive author and owner of Two Percent Survival, a website dedicated to and created in honor of the Holy Mother. Feel free to email Charles at twopercentsurvival@gmail.com.

We strive to provide the most complete and highest quality material we can for you, our readers. Although not perfect, it is our desire and prayer that you benefit from our efforts.