Our Father Prayer

Understanding the Rosary Prayers

Introduction

The Our Father Prayer is the prayer that anchors every decade of the Rosary. After the opening prayers, the person praying turns to the very words Jesus taught His disciples: “Thus therefore shall you pray: Our Father who art in heaven…” (Mt 6:9-13, Douay-Rheims). In this one prayer, a Catholic honors God as Father, asks that His Name be hallowed, His kingdom come, and His will be done. In the Rosary, the Our Father is said before each group of ten Hail Marys, so every decade begins by facing the Father with trust and humility. It reminds the person praying that the Rosary is not only about Mary, but about entering the heart of Christ and doing the Father’s will.

What Is the Our Father?

The Our Father, also called the Lord’s Prayer, is the short prayer Jesus Himself gave to His disciples when they asked Him how to pray (Mt 6:9-13; Lk 11:1-4, Douay-Rheims). In it, a person calls God “Father,” honors His Name, asks for His kingdom and His will, and then begs for daily bread, mercy, and protection from sin and evil. The Church sees this prayer as a summary of the whole Gospel (CCC 2761). Every time a Catholic prays the Our Father—at Mass, in the Rosary, or alone—it is an act of trust in God as a loving Father who knows our needs and wants our salvation. It is the basic prayer of Christian life, taught by Christ and guarded by the Church.

Why the Rosary Uses the Our Father

The Rosary uses the Our Father because the whole prayer is meant to follow Jesus and to pray with His own words. Before each decade, the Our Father places the person praying before God as a child before Father, asking for His kingdom, His will, daily bread, mercy, and protection from evil. This keeps every decade fixed on God’s plan of salvation, not just on feelings or private intentions. The Hail Marys that follow are then held inside the prayer of Christ, like children standing beside Mary while she listens to the Son. By repeating the Our Father throughout the Rosary, the Church teaches that Marian devotion always moves with, and never away from, the worship of the Father, through the Son, in the Holy Ghost.

The Our Father as a School of Christian Prayer

The Our Father is not only a set of words; it is Jesus teaching His disciples how to stand before the Father. He begins, “Thus therefore shall you pray: Our Father who art in heaven” (Mt 6:9, Douay-Rheims). In this line and the ones that follow, Christ shows what should come first in prayer: the Father’s Name, kingdom, and will, before daily needs or personal troubles. The Church says that “the Lord’s Prayer is truly the summary of the whole gospel” (CCC 2761). In it, a person learns Praise, trust, repentance, and spiritual warfare. Prayed with care, the Our Father trains the heart to think and desire as a child of God. Over time, it becomes a quiet school of faith inside every Rosary and every day.

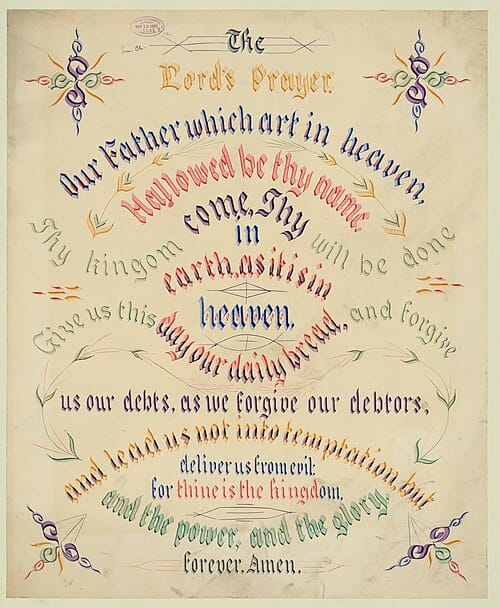

The Our Father - Full text

The Our Father is short, but its structure is clear and ordered. It begins by turning to God as “Our Father who art in heaven,” then gives three God-centered petitions: “hallowed be Thy Name,” “Thy kingdom come,” “Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven” (Mt 6:9-10, Douay-Rheims). Only after this come four petitions for our needs: daily bread, forgiveness, help in temptation, and deliverance from evil (Mt 6:11-13, Douay-Rheims). In this way, Jesus teaches that prayer starts with God’s glory and plan, then brings human needs under that plan. The text is simple enough for a child to learn, yet it holds everything a disciple needs to ask each day: worship, trust, mercy, and strength in spiritual battle.

Text of the Our Father

Our Father,

who art in heaven, hallowed be Thy name;

Thy kingdom come;

Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread;

and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us;

and lead us not into temptation;

but deliver us from evil. Amen

Main Parts: Praise, Petition, and Surrender

The Our Father holds three main movements of the Christian heart: Praise, petition, and surrender. First, Jesus leads the person praying to praise God: “Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be Thy Name” (Mt 6:9, Douay-Rheims). Before asking for anything, the soul honors who God is. Then come the petitions: for His kingdom, His will, daily bread, forgiveness, help in temptation, and deliverance from evil (Mt 6:10-13, Douay-Rheims). Here, the child of God brings real needs to the Father. Woven through these lines is surrender: “Thy will be done,” and “deliver us from evil,” both of which place life under God’s care. Prayed often, this pattern trains a person to praise first, ask with trust, and hand everything back to the Father.

Addressing God as Father

When a Catholic begins, “Our Father who art in heaven,” he is not using a title from far away, but the name Jesus gives to God. Jesus shares His own way of speaking with the Father and invites His disciples into that same trust (Mt 6:9, Douay-Rheims). The prayer says “our,” not “my,” because God adopts believers into one family in Christ. Calling God “Father” is possible only because the Son has made them children in the Holy Ghost (Rom 8:15, Douay-Rheims). The Church teaches, “We can invoke God as ‘Father’ because he is revealed to us by his Son made man” (CCC 2780). Each Our Father is a simple act of faith: God is near, personal, and able to care for His children.

The Communal "Our" in the Our Father

The first word of the prayer, “Our,” says a great deal. Jesus does not teach, “My Father,” but “Our Father who art in heaven” (Mt 6:9, Douay-Rheims). Every time a person says this prayer, he stands with the whole Church: the saints in heaven, the souls in purgatory, and believers on earth. The Church teaches that this “our” expresses the new communion Christ creates among those who believe in Him (CCC 2790). A person does not come before God alone, but as a member of His family, sharing needs and graces with others. This also checks selfish prayer. When someone asks for “our daily bread” or “forgive us our trespasses,” he prays for his brothers and sisters at the same time, even if he is alone with his beads.

Biblical and Historical Foundations

Our Father in Scripture

The Our Father comes straight from the lips of Jesus. In Matthew’s Gospel, He teaches it in the Sermon on the Mount, after warning against empty, showy prayer: “Thus therefore shall you pray: Our Father who art in heaven…” (Mt 6:9-13, Douay-Rheims). In Luke, the disciples see Him praying and say, “Lord, teach us to pray,” and He again gives them this same pattern (Lk 11:1-4, Douay-Rheims). The Church teaches that by giving these words, Jesus shares His own filial prayer with us (CCC 2765). Every time a person prays the Our Father, he is praying in obedience to Christ’s command and with Christ’s mind. This is why the Church values the prayer so highly: it is not a human formula, but the school of prayer Jesus Himself opened.

Early Christian Worship

From the start, Christians treated the Our Father as a central prayer of worship, not just a private devotion. An early text called the Didache (first or early second century) instructs believers to pray the Lord’s Prayer three times a day, serving as a daily heartbeat of the Christian life. In the early Mass, the Our Father was closely linked to the Eucharist, preparing hearts to receive the Lord with trust and forgiveness. Many Fathers of the Church preached long homilies on each line, teaching new believers this prayer before they were baptized or admitted to the full mysteries of the altar. When Catholics pray the Our Father today—especially in the Rosary—they stand in the same line of worship as those first communities gathered around the apostles.

The Liturgy and the Mass

At Mass, the Our Father is not just added on; it is a key moment in the Eucharistic prayer. After the consecration and the priest’s prayers, the whole congregation dares to say, “Our Father who art in heaven” together, using the very words of Christ (Mt 6:9, Douay-Rheims). The Church teaches that this prayer is “the most perfect of prayers,” and in the liturgy it asks above all for the coming of God’s kingdom and the final return of Christ (CCC 2770). The embolism and the doxology that follow—”deliver us, Lord, from every evil…”—unpack the last petitions of the Our Father and prepare hearts for the sign of peace and Holy Communion. In this way, every Mass places the family of God under the Father’s care.

Catechism and Church Teaching

The Church gives the Our Father a special place in her teaching. The Catechism devotes its entire final part to explaining this one prayer line by line (CCC 2759–2865). It calls the Lord’s Prayer “the summary of the whole gospel” and the model for every other Christian prayer (CCC 2761). By giving us these words, Jesus shows both how to pray and what to desire. The Catechism explains that the seven petitions cover all our needs: for God’s glory, for His kingdom and will, and for daily bread, mercy, and protection from evil (CCC 2803–2806). When a Catholic studies the Our Father in the Catechism and then prays it in the Rosary, he is letting the Church teach him how to speak to the Father with the mind of Christ.

Meaning of the Our Father - Line by Line

Every line of the Our Father opens a new part of the Christian life. “Our Father who art in heaven” teaches trust in God as a loving Father (Mt 6:9, Douay-Rheims). “Hallowed be Thy Name” asks that His Name be honored in our words, choices, and worship. “Thy kingdom come” begs for Christ’s reign in hearts now and in glory at the end of time. “Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven” is a quiet yes to God’s plans, even when they are hard. “Give us this day our daily bread,” asks for what we truly need, both material food and the Bread of Life. “Forgive us our trespasses…” joins repentance with mercy toward others. “Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil,” asks the Father to guard us in spiritual battle.

"Our Father, Who Art in Heaven"

From the start, Christians treated the Our Father as a central prayer of worship, not just a private devotion. An early text called the Didache (first or early second century) instructs believers to pray the Lord’s Prayer three times a day, serving as a daily heartbeat of the Christian life. In the early Mass, the Our Father was closely linked to the Eucharist, preparing hearts to receive the Lord with trust and forgiveness. Many Fathers of the Church preached long homilies on each line, teaching new believers this prayer before they were baptized or admitted to the full mysteries of the altar. When Catholics pray the Our Father today—especially in the Rosary—they stand in the same line of worship as those first communities gathered around the apostles.

Divine Fatherhood and Adoption in Christ

To call God “Father” is not a nice image; it is a real gift. By nature, God is Father of the only-begotten Son. By grace, He becomes Father of those who are joined to Christ. St. Paul says that God sent “the Spirit of his Son into your hearts, crying: Abba, Father” (Gal 4:6, Douay-Rheims). In Baptism, a person is taken out of the slavery of sin and given a new life as an adopted child in Christ (Rom 8:14-17, Douay-Rheims). The Catechism teaches that we can call God Father because His Son shares His own prayer with us (CCC 2780). Every time a Catholic says the Our Father, he stands in this grace of adoption, speaking to the Father with the confidence of a son or daughter.

"Hallowed Be Thy Name"

When we say “Hallowed be Thy Name,” we ask that God’s Name be held holy in every place and in every heart. God’s Name is already holy in itself, but Jesus teaches us to beg that it be known, loved, and honored on earth as it is in heaven (Mt 6:9, Douay-Rheims). This touches the second commandment, which forbids taking the Lord’s Name in vain, and calls us to bless His Name instead. The Catechism explains that this first petition asks that God be known as He is, and that our life match our prayer (CCC 2807–2811). In practice, a person honors God’s Name by speaking of Him with reverence, avoiding careless or angry use of His Name, and living in a way that leads others to praise Him.

Reverence, Praise, and Daily Holiness

“Hallowed be Thy Name” is not only said in Church. It asks that God’s Name be honored in the concrete details of each day. Reverence begins on the lips: refusing to use the Lord’s Name in anger or as a joke, and choosing instead to bless and thank Him (cf. Ex 20:7). Praise grows when a person takes time, even briefly, to say, “Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost,” during work, rest, or family life. Daily holiness means living in a way that does not contradict the prayer. The Catechism teaches that God’s Name is hallowed when our lives are made holy by His grace (CCC 2814). Every time someone prays the Rosary with care, this petition quietly shapes speech, habits, and choices.

"Thy Kingdom Come"

When a person prays “Thy kingdom come,” he asks that God’s reign spread in his own heart, in the Church, and in the whole earth (Mt 6:10, Douay-Rheims). Jesus began this kingdom in His preaching, His Cross, and His Resurrection. It is present wherever He is obeyed in faith and love, especially in the sacraments. At the same time, this petition looks toward the final coming of Christ in glory, when God will be “all in all” (1 Cor 15:28, Douay-Rheims). The Catechism explains that we ask both for the growth of holiness now and for the return of the Lord at the end of time (CCC 2818–2821). Each Rosary decade prayed with this in mind becomes a quiet plea: “Lord, reign in me, in my family, in your Church, and hasten your coming.”

Hope for Christ's Reign in Hearts and History

“Thy kingdom come” is a prayer of hope, not despair. It looks first to the heart: Christ wishes to reign in thoughts, desires, and choices by grace. When a person obeys His word, forgives enemies, loves the poor, and receives the sacraments, the kingdom is already at work. This petition also stretches out over history. The Church knows that wars, sin, and confusion do not have the last word. She remembers that Christ will return to judge the living and the dead, and that His kingdom will have no end (cf. 2 Pet 3:10-13, Douay-Rheims). The Catechism teaches that by praying for the kingdom, believers hasten the Lord’s coming by their prayer, witness, and penance (CCC 2816). Each Our Father joins that steady hope.

"Thy Will Be Done on Earth as It Is in Heaven"

When a person says, “Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven,” he places his life inside the obedience of Jesus. These are the words the Lord first taught in the Our Father (Mt 6:10, Douay-Rheims) and then lived in Gethsemane: “not my will, but thine be done” (Lk 22:42, Douay-Rheims). In heaven, the angels and saints do God’s will with joy and without delay. This petition asks that the same loving obedience take shape in our homes, parishes, and work. The Catechism teaches that we ask for the grace to do God’s will and to remain faithful even in suffering (CCC 2822–2823). Prayed in the Rosary, this line gently forms a habit: to trust the Father more than our own plans.

Trust, Obedience, and Surrender in Daily Choices

“Thy will be done” becomes real in the small decisions of each day. Trust means believing that the Father’s plan is wiser and kinder than our own, even when we do not see how. Obedience shows in concrete steps: keeping the commandments, staying faithful to Sunday Mass, speaking truth when a lie would be easier, choosing purity when temptation presses. Surrender is not passive. It is the choice to say, “Lord, if You allow this cross, I accept it with You,” and then to take the next right step. The Catechism teaches that Christ came “not to do his own will, but the will of him who sent him” (CCC 2824). Each time we pray the Our Father, we ask for that same heart.

"Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread"

“Give us this day our daily bread” teaches a childlike way of asking for what is needed today (Mt 6:11, Douay-Rheims). First, it includes ordinary needs: food, work, health, and the means to care for family. Jesus wants His disciples to bring these needs to the Father with trust, not anxiety. At the same time, the Church hears in this line a deeper hunger. We ask for the “super-substantial” bread, a hint toward the Holy Eucharist, where Christ gives Himself as the Bread of Life (cf. Jn 6:35, Douay-Rheims; CCC 2837). This petition fights both worry and greed. It is not “make me rich,” but “give us what we truly need today.” Prayed in the Rosary, it keeps the heart simple, grateful, and turned toward the altar.

Material Needs, the Poor, and the Eucharist

“Give us this day our daily bread” is never only about “me.” When a person asks the Father for daily bread, he is asking for all who lack work, food, shelter, or safety. This line should stir concern for the hungry and move the heart toward concrete acts of mercy, because a child of God cannot be at peace while others go without. At the same time, the Church hears in “daily bread” a desire for the Eucharist, the Bread of Life who feeds the soul with Christ Himself (cf. Jn 6:35, Douay-Rheims; CCC 2835–2837). At Mass, rich and poor receive the same Lord at the same altar. Praying this petition in the Rosary can lead a person both to trust God with his needs and to share generously with those who suffer.

"And Forgive Us Our Trespasses"

When a person prays, “And forgive us our trespasses,” he admits that he has sinned and needs mercy. Jesus places this petition at the heart of the Our Father, because no one stands before God by his own goodness (Mt 6:12, Douay-Rheims). “Trespasses” are real offenses against God and neighbor in thought, word, deed, or neglect. With these words, the child of God comes as a debtor asking the Father to cancel a debt he cannot pay. The Catechism teaches that this plea is astonishing, because God freely forgives sins through the Cross of Christ and the sacraments, especially Confession (CCC 2839–2840). Each time this line is prayed in the Rosary, it can be a small examination of conscience and a step toward a fuller return to the confessional.

Mercy, Confession, and Healing of Sin

“Forgive us our trespasses” points straight toward God’s mercy and the Sacrament of Penance. Jesus came “to seek and to save that which was lost” (Lk 19:10, Douay-Rheims). He not only cancels guilt; He heals the wounds sin leaves in the heart. The Catechism teaches that our sin is always against God first, but He offers pardon through the ministry of the Church (CCC 1441–1442). Regular Confession is not for “holy people,” but for sinners who want to begin again. In the confessional, a person names his sins with honesty, receives absolution, and starts over with grace and a clear conscience. Prayed in the Rosary, this petition can lead someone who has been away for years to take the concrete step of returning to Confession and letting Christ restore him.

"As We Forgive Those Who Trespass Against Us"

These words are the most searching part of the Our Father. When a person says, “as we forgive those who trespass against us,” he asks God to treat him the way he treats others (Mt 6:12, Douay-Rheims). Jesus adds a clear warning: “If you will not forgive men, neither will your Father forgive you your offences” (Mt 6:15, Douay-Rheims). The Catechism teaches that this petition is “astonishing” because God’s mercy cannot reach a heart that closes itself to others (CCC 2840). Forgiveness does not mean calling evil good or ignoring real wounds. It means choosing, with grace, to let go of revenge and to pray for the one who harmed us. Each Rosary becomes a chance to place hard memories before the Father and ask for the grace to forgive.

Forgiveness, Reconciliation, and Peace

Real peace begins when forgiveness moves from words to action. The Our Father links God’s mercy to our mercy toward others: we ask to be forgiven “as we forgive those who trespass against us” (Mt 6:12, Douay-Rheims). This does not erase justice or the need for clear boundaries, but it refuses hatred and revenge. Sometimes forgiveness can be given silently before God; at other times, the Lord invites a step toward reconciliation, if it is safe and truly possible (Mt 5:23-24, Douay-Rheims). The Catechism teaches that forgiveness “opens our hearts” and draws us closer to the Father’s own heart (CCC 2844). As this habit grows, the Holy Ghost calms anger, heals bitterness, and gives a deep interior peace that does not depend on others changing.

"And Lead Us Not into Temptation"

When a person prays, “And lead us not into temptation,” he is not asking God to stop loving him or to push him toward sin. Scripture is clear: “God is not a tempter of evils, and he tempteth no man” (Jas 1:13, Douay-Rheims). This petition asks the Father to guard His children when trials and temptations arrive, so that they are not overcome. The Catechism explains that we are asking for the grace to discern between a test that can strengthen faith and a temptation that could destroy it (CCC 2846). We also ask to be kept away from times, places, and choices that we are too weak to face. Prayed daily in the Rosary, this line trains the heart to be humble, watchful, and quick to call on God’s help.

Spiritual Trials, Sin, and Watchfulness

Life brings both trials and temptations. Trials are crosses and difficulties that God allows for our growth. Temptations are invitations to sin from the flesh, the world, and the devil. Jesus tells His disciples, “Watch ye, and pray that ye enter not into temptation” (Mt 26:41, Douay-Rheims). This watchfulness means knowing our weak points, avoiding near occasions of sin, and turning quickly to prayer when attraction to sin appears. The Catechism teaches that we ask God for “the spirit of discernment and of strength” in these moments (CCC 2847). A person who prays the Our Father with open eyes does not panic when trials come, but asks, “Lord, help me not fall,” and then chooses concrete steps away from sin: a different website, a changed conversation, a visit to the confessional.

"But Deliver Us from Evil"

“But deliver us from evil” is a cry for rescue. Here, “evil” means both the harm caused by sin and the evil one, the devil, who seeks to separate souls from God (cf. 1 Pet 5:8, Douay-Rheims). On our own, we are not strong enough for this fight. So the Church prays that the Father will free His children from the power of Satan, from grave sin, from despair, and from final loss of heaven (CCC 2850–2854). This petition stretches over the whole Church and each person’s life. It includes dangers we see and those we do not see. When a Catholic slowly prays these words in the Rosary, he entrusts himself, his family, and the dying of that day to the Father’s protection in Christ.

Christ's Victory over the Devil and Fear

“Deliver us from evil” rests on a sure fact: Christ has already won the decisive victory over the devil. Scripture says that the Son of God “appeared, that he might destroy the works of the devil” (1 Jn 3:8, Douay-Rheims). By His Cross and Resurrection, Jesus breaks the slavery of sin and death and frees those who were held in fear (Heb 2:14-15, Douay-Rheims). The Catechism teaches that Satan’s power is not infinite and that his defeat has already begun (CCC 2853). This does not remove every struggle, but it changes the ground on which a Christian stands. A Catholic does not pray the Our Father from a place of panic, but from trust in a victorious Lord. Each Rosary said with faith becomes a calm “yes” to Christ’s triumph and a quiet rejection of fear.

The Our Father and the Rosary

In the Rosary, the Our Father is like the doorway into each mystery. After the opening Creed and prayers, the Our Father is said on the first large bead, and then again before every decade. This keeps the whole Rosary standing on the prayer that Jesus Himself taught (Mt 6:9-13, Douay-Rheims). Before a single Hail Mary is said for a mystery, the person praying first turns to the Father, asking for His Name, kingdom, will, daily bread, mercy, and protection. The Hail Marys then follow inside that trust. In this way, the Rosary is not only a Marian devotion, but a steady return to the Father through the Son, in the Holy Ghost. Each Our Father resets the heart and keeps the beads from becoming empty repetition.

Where the Our Father Occurs in the Rosary

The Our Father appears at key points all through the Rosary. After making the Sign of the Cross and praying the Apostles’ Creed on the crucifix, the first large bead is for the Our Father. This begins the prayer as Jesus taught. Then, before each of the five decades, there is another large bead. On every one of these, the Our Father is prayed again before the ten Hail Marys of that mystery. In a standard five-decade Rosary, this means the Our Father is said at least six times. Some people also add it in special opening or closing prayers, depending on local custom. Wherever it appears, the pattern is the same: the Rosary moves forward only after returning to the words “Our Father,” like a child taking the Father’s hand before each step.

The Our Father as the "Gate" to Each Decade

The Our Father stands at the entrance of every decade like a gate. Before a person begins the ten Hail Marys, he stops on the large bead and turns first to the Father with the words Jesus taught (Mt 6:9-13, Douay-Rheims). This short pause is not a formality. It gathers the mind, offers the mystery about to be prayed, and places it under the Father’s will, kingdom, and mercy. Then the Hail Marys follow, held inside that act of trust. Prayed this way, each decade begins with an intentional “yes” to God before any petitions or meditations. When someone is distracted or tired, the Our Father at the start of a new decade becomes a fresh beginning, a chance to take the Father’s hand again and walk through the mystery with Him.

Uniting the Our Father with Each Mystery (H3)

The Our Father can be quietly joined to each mystery so the whole decade becomes an act of trust in the Father. As a person announces, for example, the Annunciation, he can think: “Father, let Your will be done in my life as it was in Mary’s.” During the Sorrowful Mysteries, “Thy kingdom come” can be offered for those who suffer, asking that Christ’s reign of mercy reach them through the Cross. In the Glorious Mysteries, “deliver us from evil” can be prayed for the dying and for souls in danger. The same petitions are on the lips in every decade (Mt 6:9-13, Douay-Rheims), but the intention can vary according to the scene. This keeps each mystery not only remembered, but offered to the Father with faith.

Offering the Our Father for the Church and the World

Because the Our Father begins with “our,” it is never only a private prayer (Mt 6:9, Douay-Rheims). Each time a person prays it, he can quietly place the whole Church and the needs of the world into its petitions. “Hallowed be Thy Name” may be offered for missionaries and for those who do not yet know God. “Thy kingdom come” can be prayed for the Pope, bishops, priests, and for true renewal in parishes. “Give us this day our daily bread” reaches the hungry, the unemployed, and those in war. “Deliver us from evil” covers persecuted Christians and all in spiritual danger. The Catechism teaches that the Our Father is the prayer of the whole People of God (CCC 2767). Prayed in the Rosary, it becomes a simple way to carry many souls to the Father.

Learning to Pray the Our Father

from the Heart

To pray the Our Father from the heart, a person must move from saying it fast by habit to saying it with faith and attention. A simple way is to slow down on purpose. Pause slightly at “Father,” “kingdom,” “will,” “bread,” “forgive,” and “deliver,” and think, “Do I really want this?” From time to time, pray one Our Father very slowly, maybe outside of the Rosary, letting each line touch a real part of life: family, work, sin, worries, and hopes. The Catechism teaches that the Holy Ghost makes our hearts able to say “Abba, Father” (Rom 8:15, Douay-Rheims; CCC 2766). Ask Him before you begin: “Holy Spirit, help me pray this well.” Little by little, the prayer will feel less like a formula and more like a real conversation with the Father.

Preparation Before the Our Father

Before saying the Our Father, it helps to pause and remember who is being addressed. Even a brief moment of silence can change the whole prayer. A person might close his eyes, slow his breathing, and call to mind that the Father sees him and loves him. If possible, he can set aside distractions: put down the phone, turn off the noise, and sit or kneel with simple attention. It can also help to offer a clear intention: “Father, I offer this Our Father for my family,” or “for someone who is suffering.” The Catechism says that prayer is a raising of the heart to God (CCC 2559). That raising begins before the first word. In the Rosary, this short preparation before each Our Father makes the prayer more sincere and less automatic.

Slowing Down and Praying with Attention

Many Catholics can say the Our Father in a few seconds, almost without thinking. To pray it well, it helps to go against that habit. A person can decide, “This time, I will pray more slowly.” He might give each phrase its own breath: “Our Father / who art in heaven / hallowed be Thy Name…” (Mt 6:9, Douay-Rheims). If the mind wanders, he does not panic. He comes back to the words and starts again with calm honesty. From time to time, he may pray one Our Father more slowly than usual, even outside the Rosary, letting a single line stand out in his day. The goal is not a special feeling, but a real meeting: a child speaking with the Father, with clear and careful attention.

Personal Intentions and the Our Father

The Our Father is a perfect place to bring personal intentions, but in a way that follows Jesus’ words. Before praying, a person can say, “Father, I offer this Our Father for…” and name a person, need, or fear. Then he lets each line touch that intention. “Thy kingdom come” can be offered for a child who has left the faith. “Give us this day our daily bread” may hold worries about bills, work, or health. “Forgive us our trespasses” can be prayed for a broken friendship. In this way, personal needs are not outside the prayer but are placed within the petitions Christ gave (Mt 6:9-13, Douay-Rheims). The Father already knows these concerns, but He is pleased when His children trust Him enough to speak of them.

Using Silence Before and After the Our Father

Silence can turn the Our Father from a rushed habit into a real meeting. Before the prayer, a brief pause lets the heart remember: “I am about to speak to my Father.” A person may close his eyes, breathe slowly, and place himself in God’s presence, even if only for a few seconds. After the last “Amen,” another moment of quiet allows the words to sink in. In that stillness, he can listen and notice what line stayed with him: “Thy will be done,” “Forgive us,” or “Deliver us from evil” (Mt 6:10-13, Douay-Rheims). The Catechism says that vocal prayer should “spring from a personal faith” (CCC 2704). A frame of silence before and after the Our Father helps that faith come forward.

Living the Our Father Daily

The Our Father is not only for the Church or the Rosary. It is a pattern for living each day. “Hallowed be Thy Name” calls a person to speak about God with reverence and to avoid using His Name carelessly. “Thy kingdom come” invites choices that let Christ reign at home, at work, and in hidden moments of the day. “Thy will be done” guides decisions about money, time, and relationships. “Give us this day our daily bread” teaches trust when bills, health, or work are uncertain (Mt 6:9-11, Douay-Rheims). “Forgive us… as we forgive” calls for patience and mercy in family life (Mt 6:12, Douay-Rheims). When someone tries to live what he prays, the Our Father slowly shapes his thoughts, habits, and loves.

Forgiving Others as We Are Forgiven

To live “forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive…” a person must let mercy touch real relationships (Mt 6:12, Douay-Rheims). A simple first step is to name the hurt before God: “Father, this is what they did.” Then, with the will, say, “For Jesus’ sake, I choose to forgive,” even if feelings still ache. Sometimes it may be wise to write a letter never sent, or to speak calmly when the time is right. Other times, forgiveness stays between the soul and God, especially when contact would be unsafe. Jesus warns against holding on to grudges (Mt 18:21-35, Douay-Rheims). The Catechism teaches that the heart “that offers itself to the Holy Spirit” can forgive as Christ forgives (CCC 2842). In practice, this often means many small acts of surrender, repeated until peace grows.

God's Will in Ordinary Duties

“Thy will be done” usually takes shape in simple duties rather than dramatic moments. A person seeks God’s will first by staying faithful to his state in life: prayer, Sunday Mass, family responsibilities, honest work, and the commandments (Mt 6:10, Douay-Rheims). Before a task, he can say, “Father, I do this with You and for You.” That may mean changing a diaper with patience, answering emails honestly, driving without anger, or caring for an aging parent with respect. When plans fall apart, he can quietly add, “Jesus, I trust in You,” and look for the next small step of love. The Catechism says that holiness grows through daily fidelity (CCC 2013). Lived this way, ordinary life becomes the place where the Our Father is carried out hour by hour.

Resisting Temptation and Asking for Protection

When a person prays, “lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil,” he admits that he cannot stand alone. Jesus warns, “Watch ye, and pray that ye enter not into temptation” (Mt 26:41, Douay-Rheims). Resisting sin is not only a matter of strong will. It begins by asking the Father for light to see danger early, and for strength to turn away when it appears. The Catechism teaches that this petition asks for the Spirit of discernment and power in the face of trials and seductions (CCC 2846–2847). In practice, this means avoiding near occasions of sin, using the sacraments often, and calling on the holy Name of Jesus and the prayers of Our Lady. The Our Father becomes a daily shield for the soul and for those we love.

Frequently Asked Questions

It is common to slip into "autopilot," especially with prayers learned long ago. This is a weakness, not a reason to give up. God sees the effort it takes to show up and pray, even when the mind is tired. At the same time, Jesus warns against "much speaking" without the heart (Mt 6:7, Douay-Rheims). A simple response is to renew attention in small ways: slow down one Our Father, emphasize "Father" or "Thy will be done," or offer one decade for a clear intention. When you notice a distraction, turn back to the words without harshness. That turning itself pleases God.

The original Gospel texts use words that can mean "debts" (Mt 6:12) and "sins" (Lk 11:4, Douay-Rheims). When the Our Father entered common English prayer, older translations used "trespasses" to express real offenses against God and neighbor. Over time, this wording became the familiar form in Catholic and many other English-speaking churches. The Church does not insist on one English word; "debts," "sins," and "trespasses" all point to the same truth: we owe God a debt of love, we have failed, and we ask for His mercy.

Yes. The Rosary is a vocal and mental prayer, not a race. It is good to pause for a moment on the Our Father, especially if a word or line touches something in your life. You might stop briefly after "Thy will be done" or "Forgive us our trespasses" and speak to the Father in your own words. If you are praying alone, you are free to linger as long as you need. In a group, shorter pauses are usually best, out of respect for others. In both cases, the goal is the same: to pray with the heart, not only with the lips.

Yes. Any baptized Christian, and even someone simply seeking God, may join in praying the Our Father during the Rosary. It is the prayer Jesus Himself gave to all His disciples (Mt 6:9-13, Douay-Rheims), and many non-Catholic Christians already use it daily. There is no Church rule that limits this prayer to Catholics. If a non-Catholic is not comfortable with the Hail Mary or other parts of the Rosary, they can still join wholeheartedly in the Our Father and the Glory Be. This can be a gentle way to share prayer and entrust one another to the Father.

Struggling with a line in the Our Father is not a failure; it is an invitation. Do not skip the line. Instead, slow down and tell God the truth: "Father, I say these words, but I do not fully understand or accept them yet. Help me." You can bring that line to quiet prayer, read a short explanation in the Catechism, or speak with a priest or trusted Catholic friend. In the meantime, keep praying the whole prayer with humility. The Lord can use that honest struggle to deepen faith.

Links

Charles Rogers is a resident of South Carolina and a retired computer programmer by trade. Raised in various Christian denominations, he always believed in Jesus Christ. In 2012, he began experiencing authentic spiritual encounters with the Blessed Virgin Mary, which led him on a seven-year journey at her hand, that included alcohol addiction, a widow maker heart attack and death and conversion to the Catholic Faith. He is the exclusive author and owner of Two Percent Survival, a website dedicated to and created in honor of the Holy Mother. Feel free to email Charles at twopercentsurvival@gmail.com.

We strive to provide the most complete and highest quality material we can for you, our readers. Although not perfect, it is our desire and prayer that you benefit from our efforts.